“In his last visit to the Shlomo region, the Prime Minister returned and promised that ‘the Israeli government is firm in its decision to maintain under its authority the continental continuum from the mandatory border of Eilat to Ras Muhammad,'” this was published in February 1976 in the “Davar” newspaper. It was a quote from the words of Yitzhak Rabin. During his first term as prime minister, settlements and tourism projects were built in the Sinai Peninsula, including the Naama field school in Sharm el-Sheikh.

The planning of the school was undertaken by the architect Israel Godovitz, who chose to build it using industrialized buildings, a move that was an innovation for his time. The school existed for five years until Menachem Begin seized power and eliminated the settlement in the area as part of the peace process.

(1) The planning

“It all started with the Society for the Protection of Nature, which decided to establish field schools in remote places, and Sharm el-Sheikh was the end of the country to the south,” recalled architect Israel Godovitz in the story of the project he designed in 1975. “The site that was chosen was near a diving site in Naama Bay. Not long before, the road that went south from Eilat was paved and was a continuation of road 90, which reached Taba, Nuaiba and Sharm el-Sheikh. I was then in charge of planning at the Ministry of Housing [Godovitz worked at the Ministry of Housing from 1966 -1974, MI] and the Society for the Protection of Nature received its budget from the settlement budget that belonged to the Ministry of Housing.

After the Six Day War, says Godovitz, when many territories were added to the state, the Society for the Protection of Nature initiated the establishment of field schools in those territories. Besides Sharm, the company-initiated schools in Santa Katrina (which was called “David’s Cliffs” after David Tamir, the pilot son of MK Shmuel Tamir), in the Yamit region, Gush Etzion, and in Ramot in the Golan Heights. Schools were also established in an area that had not been occupied for a long time A field like in Hatzava (which Godovitz also designed) and Ein Gedi (where Godovitz designed the extension). These projects were won by Asael Ben David, who was the director of the construction department of the company for the Nature Conservation Society. The choice of the site in Sharm was made by the Nature Conservation Society, crater area in a semicircle.

“The projects I got to plan were the projects in places where there was no contractor willing to go to them. This was the case in Sharm and the same was the case in Hatzava and Ramot. A school was also built in Santa Katrina, but there Sacheko [architect Saadia Mendel, MI] built with the construction of the Bedouins from palm leaves and stones and there was no need for a contractor. In Ramot they finally found a contractor, but in Hatzava and Sharm there was no one willing to come down any distance. There was only a poor and miserable fishing village. So something had to be invented.

“There was a small construction company of three young guys, Yehezkel Nussbaum, Haim Giron and Elimelech Mayblom, who had a block factory in Nes Ziona and they were looking for a breakthrough. Today, looking back, it was a matter of win win, a winning combination of an architect who wants to break through, has A budget and he has bosses who listen to what he wants. It happens once in a lifetime. The young company wanted to work as contractors and the Nature Conservation Society wanted the school. Everyone was involved in the project. It was a moment of grace. “Ashstrom was the company that connected everything. This was also the moment when Zvi Heker was able to build in the Polish mountains and he also worked with Ashstrom.

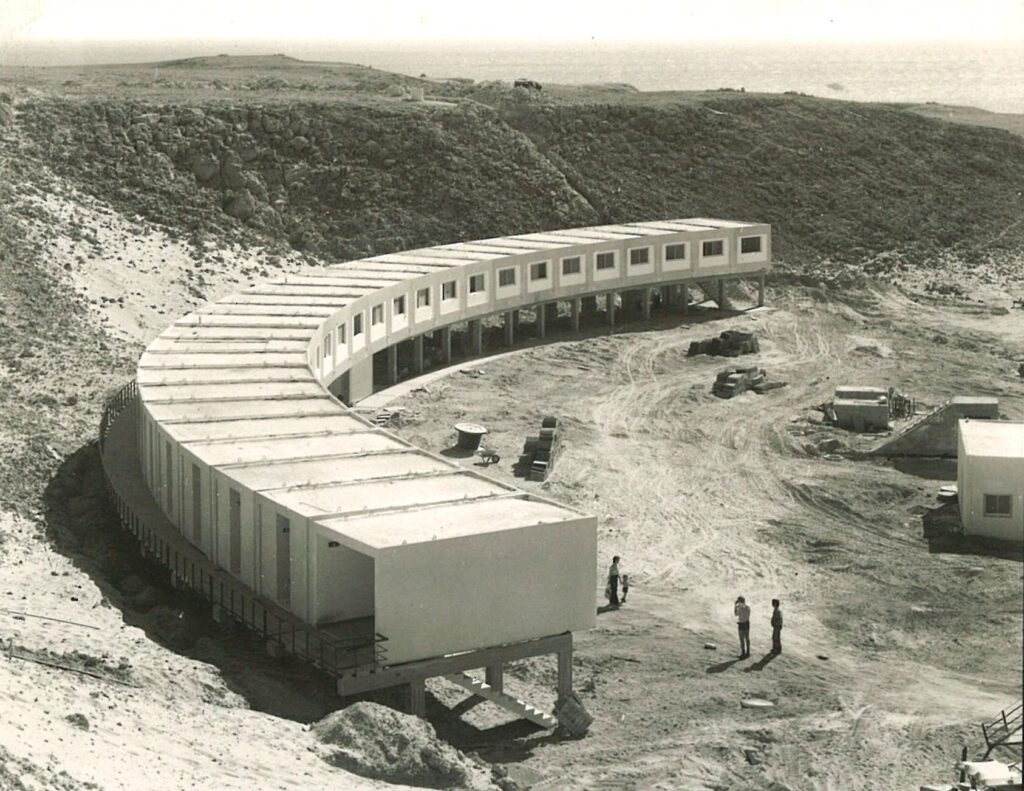

“In 1972, we received the Goldstein Award from the Israel Architects Association for an innovative contribution. Ashstrom were ready for any attempt, so much so that at the Hanukkah of the Field school in Hatzeva, Ze’ev Sharaf, who was then the Minister of Housing, took me aside and asked me, ‘Are you sure it’s prefab?’ . Where are these today? “The problem was how to manufacture the buildings in a factory in Ashdod and transport everything to Sharm. I designed buildings that are like containers. The module is just like a container: 12 meters long, 2.44 wide, 2.90 high and the structure is made of concrete. Ashstrom called them ‘Ashkobit’ which is the combination of the words Ashstrom and Kubia. Each Ashkobit had an open foyer, an entrance door and immediately after it on the right a bathroom, on the left a bathroom and in the room itself four beds and a wall closet.

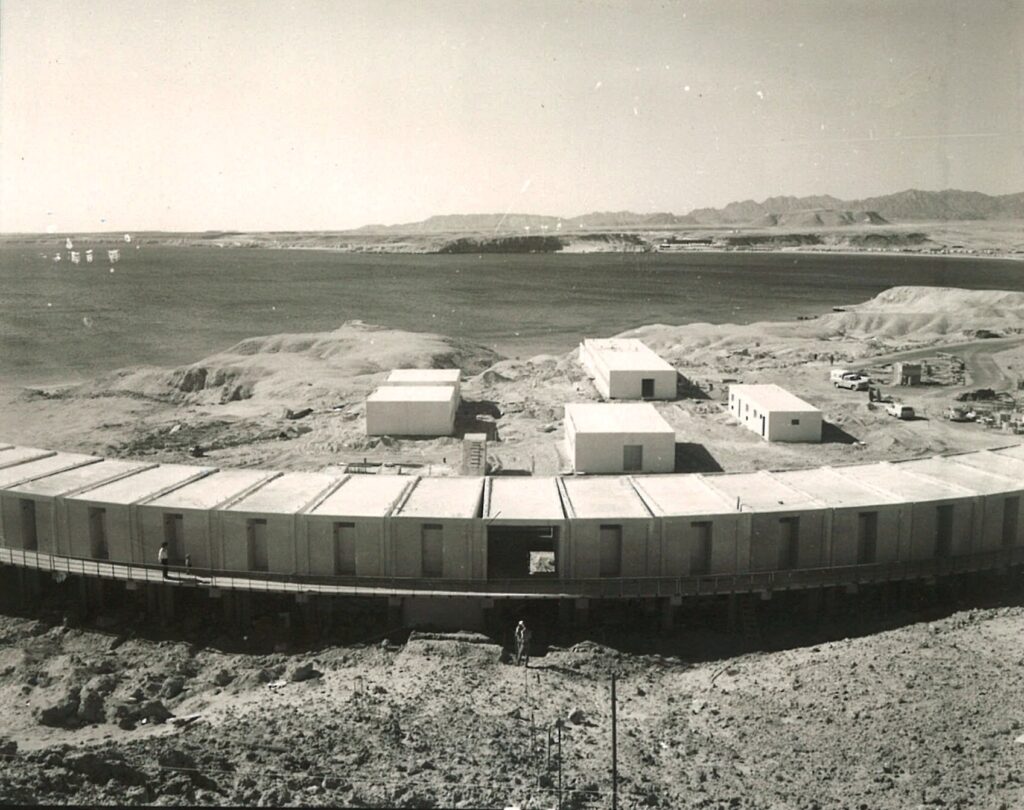

“On the site that was in the shape of a semi-circle, we put thirty Ashkobits. There should have been a dining room in the center, but we didn’t have time to build that. From the school there is a path that goes down to the sea. The big question was how to make a circle so that the Ashkobits sat exactly in the circle, after all we couldn’t get a surveyor down there and I insisted on the circle. We took a peg, a wire, a brush and a bucket of lime. I visually estimated the location of the center, stuck a peg to which I tied the wire and took a radius of 120 meters. With the brush that was at the end of the wire I marked the circle.

Since the soil in the area was flat, we didn’t take a chance to put the Ashkobits straight on the ground, but according to the markings I made with the brush and the lime, they drilled stilts and every three meters there was a post. On the pillars rested a concrete bracket on which the Ashkobits was placed and then they prayed that when they brought the Ashkobits no mistake would be discovered. The Ashkobits arrived ready in trucks. On the site they connected, and everything was ready. Shemaya ben Avraham’s office was the one that did the engineering planning.

“After the construction of the trainee residences was completed, public buildings were erected that included a dining room and classrooms built from standard precast. Later, the staff residences were built on the top peak, which were already built by the Urban Development Division of the Ministry of Housing. “Every experiment is not necessarily the most successful in the world, but it is breakthrough thinking. He breaks the usual framework. If you constantly go according to what has been, then you will never reach a solution for living.”

(2) Friend’s stories

Assaf Madmoni served as maintenance man in the early years of the Mossad. Before that he lived at the Ein Gedi field school, where he worked for the Nature Reserves Authority and lived in a building that was also designed by the architect Israel Godovitz. Later he moved to Neot HaKikar and managed the “Beit Heutzer”. Madmoni gave me a tour of the Sodom area eight years ago and following the tour I published here a series of lists about the sites we visited together: the movie cave, a spring, caves and canals, the abandoned workers’ camp of the potash factories and the citadel in the construction of the square designed by the architect Nahum Zolotov. Madmoni continues today to be involved in tourism and apart from guiding tours he also operates B&Bs in the “Salt of the Haaretz” complex in the square buildings.

“There were 24 units in rainbow, with each unit having four beds on two floors and in addition there were five two-family buildings where the 15-person staff lived,” Maddoni said, who knew the complex intimately. On the lower level, apart from the ashkobits organized in the arch, there was also an office building, a hall for activity rooms and a dining room. The landscape architect Tal Alon Mozes, head of the landscape architecture track at the Technion, was also part of the school’s team and there, among other things, she met her husband. I contacted her hoping to find photos from that time. “We didn’t have a camera, we lived in the present,” she replies.

“The school sat on two steps of the fossil reef. From the first day they thought that everything would be temporary and did not bother to remove the hooks from the ashkobits that made up the hostel and the faculty buildings that were on the top step. In the original plan, there was a lot of attention to the vegetation and the creation of a green appearance and a slightly cool microclimate, but no A lot has developed. The school and especially the staff residences were built with a view to the view, to the southern part of Naama Bay. The guest rooms had windows but no balconies and the public buildings hardly paid attention to the view.”

(3) End

The responsibility of Naama field school was sad. Less than six years since it was established, the young institution was closed. The ashkobits buildings were disconnected from the infrastructure and the ground, loaded onto trucks, and returned to Israel. Godovitz visited the site a few years ago and discovered that it remained empty.

Michael Jacobson is an architect and geographer who works in the field and writes about Israeli architecture. The article “A tour of a field school in Sharm el-Sheikh” was originally published on the “Rear Window” website:

Link to the source Here